Falling

48 years ago I was at the top of a 45-foot-tall scaffolding tower. It fell over. As I was about to die — it was obvious that I was about to die — my last words were, “Oh no, oh no.” Some time later, from a great distance, I heard someone saying, “Oh no, oh no,” and realized it was me, not dead yet. My right knee hurt, my back hurt, my head and a few other things hurt, but mostly my left ankle hurt.

A deputy from the nearby town of Tenino came rushing up to where I lay amidst a tangle of torn and fractured steel. He had been there to monitor us as we cleaned up after a rock festival. Until that moment it had been boring duty, but now he had an actual emergency to deal with. I told him that I thought I’d broken my ankle. Whipping out a huge, very sharp knife, he prepared to cut off my ridiculously expensive, much-beloved hiking boot. I pointed out that it laced down to the toe, and that he could just untie it. He was crestfallen, but he put away the knife and eased the boot off. Then he went to pull my sock off, but my ankle was now grapefruit-sized, visibly expanding, and pulling on it made for passing-a-kidney-stone levels of pain. Granted, I have never passed a kidney stone, but it seems likely that one’s pain meter is pretty well pegged when you get to the gasping-as-you-almost-faint level. I pointed out that he could cut the sock off. This really made his day. Out came that knife, and off came the sock.

What followed, in the short term, was a cast on the ankle, bandages on assorted other body parts, and slow recuperation in my parent’s basement. I taught myself to juggle, studied knots, read many books, and thought a lot about mortality.

What happened in the long term was a life: a series of ludicrous mistakes tempered by love and education. Along the way the ankle decayed, little by some, until it felt like that sock was being pulled off every time I walked on it . Eventually I had it fused, which, interestingly enough, involved someone approaching it holding a very sharp knife. The good news is that the pain went completely away. The bad news is that the adjacent joint (the subtalar, for you anatomy nerds) now took up the slack in stress, which it was not even remotely designed to handle, until it, too, became seriously decayed.

I recently had my foot X-rayed. The technician took one look at the picture, then turned to some nearby colleagues and said, “Hey guys, take a look at this!” They all crowded around, marveling. I stood on my little pedestal, in one of those charming hospital gowns. One of the techs said to me, “How can you walk on this thing?” In that moment, it occurred to me that I might have been being just a bit too stoic.

No ankle has an easy life. We expect it to bear up under our entire body weight (okay, minus the foot), and to articulate in all directions, dealing with major levels of impact and static loads, in torque, shear, tension, and compression, sometimes simultaneously, and to do so utilizing a laughably small surface area, with amusingly short lever arms. Accordingly, it is a very easy joint to damage, and a very difficult joint to repair, which is why surgeons are much more likely to recommend fusing a badly-damaged ankle than installing a prosthesis, unless the owner of the ankle is a particularly lethargic couch potato. To an active person, they are likely to say, “We could give you a new ankle, but compared to a hip or knee replacement, the hardware is flimsy. You would probably break it.” That is what they told me, hence the fusion. After the passage of years, with the doctors working on the I-hope-mistaken assumption that I am less active and/or more careful than I used to be, plus advances made in hardware, they are now graciously willing to install a new ankle joint.

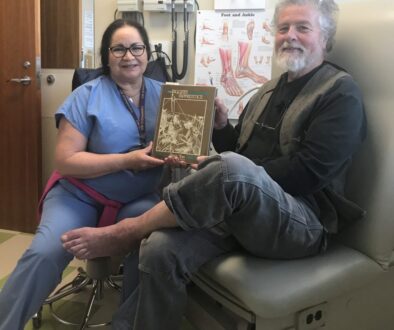

Which brings us up to date. Christian and I have just finished one type of journey, and now I’m about to embark on a different type; in about a week I’ll be in an operating theater in Seattle, having some hardware installed. It is apparently a tricky operation, and this version of it has been done only a few hundred times, anywhere. I am not looking forward to the operation, but I am looking forward to writing about it.