Scrubs

Seattle is a hilly place. If you head east from downtown, the first hill you come to is First Hill. That is the official name, but although I grew up in Seattle I never heard it called anything other than Pill Hill, which is as accurate as it alliterative; the place is infested, drenched, chockablock, laden, dense, encrusted with all things medical. There are clinics, offices, labs, supply stores,research institutes, etc., and of course there are hospitals, great grand multi-story hives of allopathically-intensive activity.

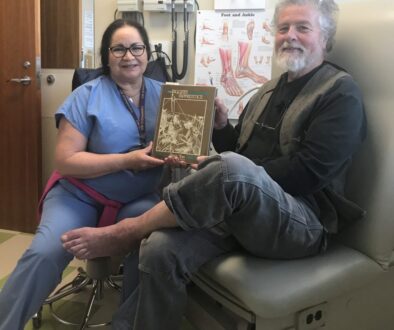

Nurses work here. And surgeons and orderlies and lab technicians. Phlebotomists, anesthesiologists, optometrists, and all the other ists. Specialists, and generalists (but especially specialists), an army of people who work, right down to the molecular level, on human bodies.

Here you will also find people who manage all of those people, who do their accounting, keep their records, order and deliver the things they need, and who feed, clothe, transport, and clean up after them. The people and the structures comprise an ecosystem that is immense, complex, dynamic, and yes sometimes hideously expensive for the customers. I have no desire to go into the socio-economic mess that is US medicine, other than to say that because I have attained a certain age, and because we once had a rational, compassionate President, I will be able to get my ankle fixed, and thereby continue to lead a satisfying, productive life for longer than I otherwise would have. For the moment, though, I’d like to talk about scrubs.

People in Seattle typically wear colors that can be a found on the underside of a mushroom. But as you go up onto the Hill the palette shifts to the industrial pastels of surgical scrubs. At the center of things, at certain times of the day, regular street wear can seem out of place, because you are surrounded by people wearing the only uniform I can think of that doesn’t try to emphasize aspects of physique, or give an impression of competence and efficiency. It is a shambly, shapeless excuse for a uniform. If you had never seen one before, you would laugh and say, “Why are these people walking around in their pajamas?” But no one laughs, because these loose, thin garments proclaim that the wearers keep human metabolisms running. The sight of these garments elicits an instant, if queasy respect for the wearers, reminds us that we are fragile, mortal creatures, and that a test or an injection or an incision or a focused blast of energy from one of these people might restore our health, or even save our life.

One thing that scrubs have in common with other uniforms is that they are suited to a particular work environment. So they are loose-fitting because the work can make serious demands on physical exertion and range of motion, and thin because a hospital is a climate-controlled environment, and one in which exertion and mobility can cause one to work up a sweat, which is not always avoidable but which is discouraged, Patients, of course, are expected to sweat — and bleed and produce assorted other effluents and exhalations that compromise the overarching need for obsessive cleanliness — which is why scrubs are also easy to remove, cheap, and able to stand up to repeated, harsh washing.

One other way that scrubs are like other uniforms is that they mark the wearer as a member of a group. This can, it is true, diminish the significance of individuals, and encourage conformity, detachment, a cold uncaring. But it is at least as likely to engender a feeling of purpose, of belonging to something larger than oneself. People can achieve competencies and autonomies in the right group, things not available to loners; when you act in isolation, you lack context. When you have a rich context, you can become more fully human, and therefore humane. This matters in the world of medicine, an art so profoundly intimate that it becomes literally — but not, we hope, emotionally — sterile. You don’t want some heartless cypher in charge of your well-being.

This morning my legs will be the subject of a hyper-computerized portrait, a template for the surgeons who will be rebuilding my ankle. The machinery for this will take center stage, but the people who guide me to it, and tell me where to stand, and operate it, and analyze the results, will provide every bit of meaning to the exercise. They’ll be members of a modern tribe of healers, and they will be wearing scrubs.