The Parable of the Parrel

Some square-rig sailors were talking about interesting problems they’d encountered while under sail. Given the hazards of the marine environment, the complexities of the rigs, and the huge forces that move through those rigs, the stories tended towards the scary/hilarious. It’s amazing how much trouble one can get into when confronted with high winds, steep seas, huge sails, and several miles of running and standing rigging.

One deeply experienced skipper was describing what happened when, in an extremely lumpy, storm-driven sea, the fore course yard parrel on his boat let go. The parrel, on pre-19th-century-style ships, is essentially a massive, very formally-constructed lashing. It holds the yard to its mast, yet allows the yard to pivot and tilt. If a parrel breaks, the yard might still be suspended at its middle by the tie or halyard, as well as by the lifts at its ends. It will also restrained from below by the braces, and by the sheets at the lower corners of the sail when it is set. But even with all these attachments intact, failure of the parrel means that the yard, which in this case weighed about a ton, can and will slide a good ways laterally as well as swinging fore and aft, bashing the mast and tearing up assorted gear, both its own and that of adjacent spars and sails. That’s why, in this instance, a brave and experienced hand went very carefully aloft to constrain the yard. Essentially the task was to lasso the damn thing and lash it to the mast.

All eyes were on him as he struggled to build a jury rig without getting crushed. “And of course,” said the skipper telling the story, “it’s especially bad when something like that happens,” at which statement everyone nodded in agreement, except for a young deckhand who was listening in, who looked puzzled and asked, “Why’s that? Because the crewmember was in danger? Because the sail can carry away? Because the yard can break, or the parrel get caught in the –” “No, no,” chorused several old salts, and then the first skipper explained, “It’s because that’s when the generator catches fire.”

Now the young deckhand was really puzzled, and asked “How could a parted parrel have anything to do with a flaming generator?”

“I’ll get to that in a minute,” replied the skipper. “First, let’s take a look at how the yard got loose.

“It takes layers of protection to avoid mishaps. In the case of the lower yard parrel, there was first a redundancy in scantlings. That is, the materials were way stronger than the loads required. In addition, the yard was part of a system comprising several other yards, as well as sails without yards, any several of which we could get along without, and that is redundancy in components. And finally, the overlapping actions of the crew –regular inspections, cycling of materials, ongoing awareness – make for a redundancy of efforts.

“The lower yard is the most important piece in its system, since it’s the biggest, and because the other yards on that mast are sheeted to it, directly or indirectly. You can still work around it, but without that parrel it can do a lot of damage, which is why we sent someone up there to secure it. The parrel’s redundancies had failed. The surplus strength had worn away, we in the crew didn’t spot the wear, and then that storm hit, and we suffered the consequences.”

“Okay, so you’re saying that there weren’t enough redundancies in the rig, and that’s why the parrel failed.”

Not exactly. Obviously, if we’d done our job better, the yard wouldn’t have broken free in the first place, but redundancy and skill and care can never completely eliminate the possibility of failure. So I’m not talking about how important it is to keep things in optimal shape. I’m talking about what you do when things inevitably go sideways. I’m talking about a larger system, with deeper opportunities for chaos. Let’s look at the generator now.”

“At last, the generator.”

“This was one of two, both good machines, both properly maintained. Nothing the matter with them, lots of protocols and failsafes. But when they were installed, there was a flaw in how the venting was laid out. Not a major flaw; it just wasn’t optimal in terms of keeping seawater out in extreme conditions, the kind that even seagoing vessels rarely encounter.”

“And venting for extreme conditions means a lot of extra time and labor to prevent things that are probably never going to happen. Got it.”

“Exactly. It was a flaw that could only be exploited by violent vessel motion, with water pouring into places that it isn’t meant to pour, merrily shorting things out, and starting a fire. Meanwhile that yard is thrashing around, some poor sod is aloft, trying to secure it without dying, the wind is still screaming, the boat is lurching to and fro, and everyone’s attention is either on keeping the ship head to wind, or watching the drama. That’s why the only person who sees the smoke coming out of the deck, way aft, is the person aloft. He shouts, but of course no one can hear a word. He waves and points, but everyone assumes that his gestures have something to do with the yard. They’re scratching their heads and shouting at each other in an attempt to confer, and all the while that smoke is getting thicker.”

“This is just an example, isn’t it?”, says the young skipper.

“Yes, good, yes. The second catastrophe could just as easily have been someone falling down a hatch, or a line about to get wrapped in the prop, or any of a hundred other things. The point to remember is that catastrophes don’t pick on one weak spot at a time; they’re after all of them, always. So when one thing fails, even though you might have your hands really full dealing with the consequences, it might be a good idea to look around for whatever else might be failing. It’s a good thing that we finally did just that.”

“Huh,” says the deckhand, “It’s like an emergency version of being at the helm: focus on your course, but keep scanning the horizon.”

“Ahhh,” say the old hands.

This story is the first of a series of rigging parables. It is a modified retelling of an actual conversation, from some years ago, and I fear that I have forgotten the name of the captain who told it to me. If you are out there, please be in touch if you’d like attribution, and/or to correct my recollection.

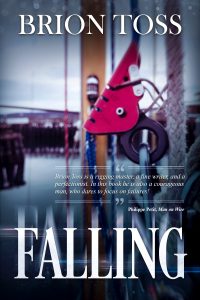

Enjoy the story? Looking for more? You’re in luck! “Falling,” which in includes this and other tales from aloft, both thrilling and amusing, is now for sale on Amazon.com in handy e-book form! Or click here to get it on Apple iBooks!

From dropped tools to collapsed towers to near-fatal falls, the litany of accidents and near-accidents is long… and the sometimes miraculous outcomes are both instructive and thought-provoking.

Not a technical manual, “Falling” is nonetheless a must-have companion in the library of anyone working at heights.