The Commodore and the Vigilant

December 23, 1931.

Ten miles off Cape Flattery, the 4-masted schooner Commodore furls its sails and picks up a towline from the tug Goliath, out of Neah Bay. It is late afternoon, blowing a gale, with waves to match. Conditions are so rough that in the process of getting the towline out the tug’s mate is injured, and has to be carried off the stern deck. The schooner manages to get the line aboard, and the Goliath gets under way, but cannot get synchronized with the schooner’s motion; the sea state is confused as well as high and steep, producing alternate slack and shock loads on the 2” steel cable. The 1,200 ft. line breaks at the tug’s chock, and the crew of the Commodore slowly hauls it aboard by brute strength. Vancouver Island is a deadly obstacle to leeward, so the schooner’s crew sets storm canvas, heaves-to, and hopes that another tug can come out to them. The Goliath heads for shore, to get help for the injured mate.

One month earlier:

The schooner Commodore is sailing out of Honolulu, bound for the Pacific Northwest. While in Hawaii, the ship offloaded over 1.5 million board feet of lumber, and it is now going home in ballast. A few days before departing, Captain Krantz and his crew host a party aboard. Among the guests is the captain of the 5-masted schooner Vigilant. It is reported that there is a bit of good-natured joshing between the two skippers, because Commodore had beaten Vigilant to Hawaii by three days.

But the two ships do not leave Hawaii together, or anything like it. Four days after the party the Commodore is heading for the Northwest. The ship is six days and over a thousand miles into its voyage by the time the Vigilant gets away on December 3rd. The Vigilant is just a few feet longer than the Commodore (241ft. vs 234), so there is nothing to suggest that the Vigilant might have spotted its rival almost a week’s head start. Far more likely, the Commodore simply finished loading ballast first, and got under way; this is a working vessel, and will be back in Hawaii early in 1932 with another load of lumber. There is work to be done. Despite this, a reporter at the Honolulu Star-Bulletin gets it into his head that the two schooners are in fact racing, and he files a report to that effect. The story goes out over the wire, and within days newspapers all over America are running stories about a non-existent race. From this point on, the papers will be posting bulletins describing a neck-and-neck race across the Pacific.

Now it is possible that the lead boat “sailed into a hole,” and was overhauled, at least somewhat. But really, calling this a race is like saying that two similar aircraft departing at separate times are racing. These boats weren’t, they were taking rocks home as ballast, because Hawaii had no cargo for them. Their purpose was to get back to the Northwest lumber mills, to pick up another million or two board feet of lumber for the construction of Pearl Harbor. But public perception is a powerful thing, and millions thrilled to the image of two grizzled captains roaring insults at each other as they pounded along, as in Kipling’s Captains Courageous, which would be made into a movie just a few years later. And other schooners were in the news at the time, like the Canadian Bluenose and the American Gertrude Thebaud, which had just completed a race series, won by the Bluenose. This was also the Great Depression, and Americans really needed a break from the bleak circumstances of their time. So the Oakland Tribune reported, at about the halfway point, that the Vigilant was just 375 miles back, but appeared to have lost its radio aerial. The Hartford Courant reported some days later that the Commodore was, “breasting the heavy swells of the Pacific tonight,” and wondering why the Vigilant hadn’t been heard from for some time. The Nanaimo Daily News said that the schooners were, “…focusing the glasses of all who admire sailing vessels,” before going on at some length about their “flash predecessors” and the “secrets of the winds.” Later on, the two skippers and their crews speak only of a grueling passage, with storms and calms all the way across the Pacific resulting in an unusually slow crossing for both vessels.

Finally, on December 22nd, the word goes out that Commodore is only 40 miles from picking up a tug at Cape Flattery, with Vigilant nowhere in sight. The Los Angeles Times, Green Bay Press-Gazette, Pittsburgh Press, and many other papers declare the Commodore the winner of the “historic race.” The acclaim is premature. Conditions are deteriorating quickly, with a building southeast wind barring the way, and in retrospect the failure of the Goliath’s towline seems inevitable. But worse is yet to come.

With night falling, and Vancouver Island looming to leeward, the schooner is met by a second tug, the Roosevelt. Built as a support vessel for Robert Peary’s Arctic explorations, and later converted to an oceangoing salvage tug, the Roosevelt has seen and survived terrible conditions in its long career, but it is now heading out into real violence. Despite this, they manage to get their towline aboard the Commodore at around 10 pm, and take up the slack. For four hours they keep at it, but can make no headway, and at last their towline too parts. This time it fails at the bow of the schooner. They try to pass the line a second time, and a third, but it is no use. By now waves are breaking into the tugboat, putting it in danger of sinking. The radio operator puts out a distress call, finishing it with: “For God’s sake hurry!” A short while later, as the radio room is flooding, he issues another, garbled message that ends, “…does not appear to have much chance to survive.” Coast Guard cutters from the U.S. and Canada rush to the area, but can find no trace of the Roosevelt, and newspapers report that it might have been lost with all hands. Happily, the crew pumps hard enough to gain a bit on the flooding, and the tug limps back into Neah Bay.

This leaves the Commodore drifting rapidly towards Vancouver Island. There is no way they can beat to weather into the narrow entrance to the Straits, so instead of finding shelter inland, the schooner must come about, fighting its way clear of the rocks to leeward. They destroy several sails and spars in the process, all of which are absolutely essential to keeping the boat pointed where it needs to go. The crew, none of whom are under fifty years old (one of whom is 72), drags replacement parts up from below, and doggedly puts things to rights as the wind tops 70 knots. At last they heave-to about 200 miles northwest of the Cape. There they stay for ten brutal days, alternately bashing about in hurricane-force winds and slamming about in brief calms, amid huge swells.

Meanwhile the Vigilant is coming up, in relative comfort, on the same wind that gave the Commodore such a beating. Things get even nicer for them as the storm eases, and the wind goes southwest. On January 4th, the now-recovered tug Roosevelt takes the Vigilant in tow, bringing it into the Straits without difficulty. About 5 hours later, the Commodore makes its weary way back to Cape Flattery, and is picked up by the Goliath. The same newspapers that had lauded the Commodore as the winner now laud the Vigilant, even though at the end they trailed in elapsed time to the Cape by an additional four days. But no matter, the papers had their race, and their readers had their thrills. Interviewed shortly thereafter, the captain of the Commodore describes accounts of the voyage as, “A bunch of you reporters trying to stir up trouble.” A crewmember of the Vigilant, writing years later, says that, “At Eagle Harbor, on Bainbridge Island, the Vigilant was declared the “winner,” though Captain Mellberg, like the crews on both schooners, had no idea they’d been racing.”

It would be easy to describe all this as a Depression-era example of fake news, but though the reporting is at least suspect in some of its details, the important truth is that some very tough human beings took some very large, ungainly, engineless ships through mountainous seas, because it was their job. Racing or not, they did the near-impossible, and then loaded up and did it again. And again.

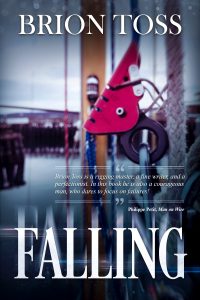

Coda: I first saw the photograph of the Commodore hanging in a cabin aboard Nancy Erley’s boat. Nancy is now one of the most deeply-experienced sailors of our time, but back then she was living aboard a classic powerboat on Lake Union, and dreaming of the sea. She told me she had no idea what ship it was, but that something about it inspired her. We now know the story, but the picture says everything that needs saying: there is you, the viewer, looking out past a rough, threatening swell, to a ship that is somehow not overwhelmed.