Ashley & Rigging, Part 1 of 2

When the New Bedford Whaling Museum decided to honor their local hero Clifford Ashley, they went all out with an exhibit titled, “Thou Shalt Knot,” filling a major gallery with the great man’s art and artifacts. They also published a sizable volume of commentary and analysis, with contributions from people like Phillipe Petit, Des Pawson, and yours truly (see below), on topics ranging from Knots in Literature, Knots and Science, family history, sociology, and much more. If you would like to learn more about the exhibition or its book, visit the Museum web site: https://www.whalingmuseum.org/explore/exhibitions/thou-shalt-knot-clifford-ashley/. If you are anywhere near New Bedford, you should really plan to stop in.

And now, the first installment:

For the rigger, knots are fasteners. They are to rigging as nails, bolts, and screws are to carpenters. The difference is that, while a nail is made by someone else, and provided to the carpenter, a knot (or splice, seizing, etc.) is a fastener that is selected from an abstract inventory of candidates, and then fabricated, on site, for each application. Up to that point, the knot exists solely as a concept in the mind of the rigger.

Because the scale and nature of the work drives the selection of the knot, the tyer should properly take loads, vectors, materials, and the nature of all other system components into consideration before picking up a piece of rope. People often have trouble learning to tie knots, but this is mere topography, and really should be the least challenging part of working with knots. That most people learn a very few knots, and then tie them without much if any thought as to their suitability is a testament to the prevalence of mild loads, strong materials, and luck. But riggers cannot count fully on any of those things. They must know how the nature of a given knot relates to the demands that will be placed upon it. They must know not just how to tie, but why.

The purpose of a good knot book, then, is to turn its readers into engineers, as well as into makers – and users – of knots. This is asking a lot, and most knot books, which concentrate almost exclusively on topography, are clearly not up to the task. The most notable and influential exception to this is the Ashley Book of Knots. Published in 1944 and never significantly updated, it is still the most beloved reference work on the topic of knotting, even though it contains none of the hundreds of practical and decorative knots which have been developed since 1944.

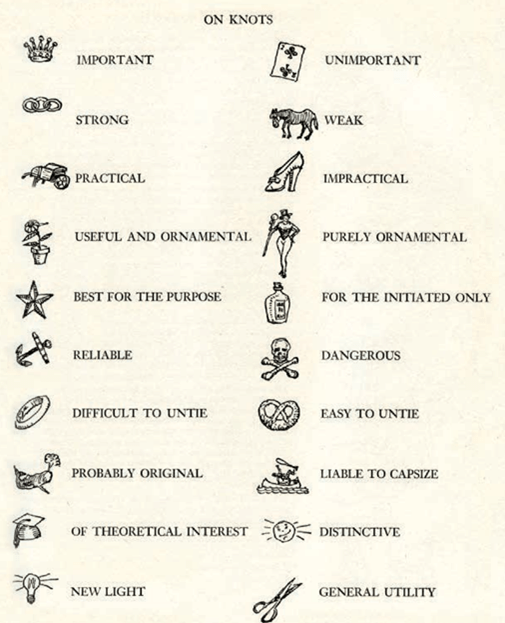

This might doom a lesser book to obscurity, but (a) it still contains enough high-quality content to reward a lifetime of study, and (b) its greatest value lies in how Ashley illuminates his subjects as to specific jobs, historical context, and especially mechanical properties. He teaches us to see knots as characters with specific traits, suited for some jobs but not others. He does this with emoji-like icons (Ashleymojis?) that run the gamut from “unimportant” to “impractical” to “for-the-initiated-only” to “liable-to-capsize”, plus 16 more. He also does this in the opening chapter (“On Knots”), which is part historical monograph, part autobiography, part research paper, part manual of lexicon, and almost incidentally, part instructional primer. The chapter, in other words, is much more about people than about knots.

This theme is continued in “Occupational Knots,” the second Chapter. There are 364 knots here, distributed among no fewer than 86 fields of human endeavor. Intriguing though the knots are, the focus is on human lives, conducted using human-made tools. Here, and throughout the book, we are carried along by illustrations that are somehow both precise and warm.

This approach encourages us to build a resilient, situation-specific vocabulary of knots, as opposed to memorizing a list. It trains us to assess the demands of each job that we want to do, in order to be able to choose the most appropriate knot(s) with which to do it.

Many of Ashley’s gifts to us have found new life in today’s world. The Buntline Hitch, for instance, is mentioned no fewer than eight times, for everything from securing corned beef to furling squares’ls, to tying neckties. Of the originally-recommended uses, only squares’l and necktie applications (#2408, commonly known as the four-in-hand) are currently in wide use. But contemporary riggers, assessing characteristics in the way of their mentor, have adopted the buntline hitch as a general-purpose halyard hitch. Think about it: it is a knot that is extremely simple, secure, compact, and about 30% stronger than a bowline. Those virtues, in many situations, outweigh its tendency to jam under extreme loads, so out of the data base it came, to find a home in contemporary ropes.

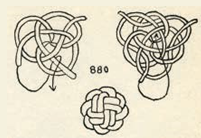

Two other examples of database adaptations are the knife lanyard knot (#787), and an original button (#880). Both of these knots were originally meant to be primarily decorative, and they are indeed lovely things. But a few years ago, riggers began making “soft shackles” in Spectra/Dyneema. These fabulously strong button-and-becket constructions have displaced steel shackles in many applications. A soft shackle that terminates in a lanyard knot, properly tied, can be counted on to hold at over 100% of the strength of the cord- age it is tied in. And the version that terminates in a two-strand version of the #880 will hold at close to 200%.

Two other examples of database adaptations are the knife lanyard knot (#787), and an original button (#880). Both of these knots were originally meant to be primarily decorative, and they are indeed lovely things. But a few years ago, riggers began making “soft shackles” in Spectra/Dyneema. These fabulously strong button-and-becket constructions have displaced steel shackles in many applications. A soft shackle that terminates in a lanyard knot, properly tied, can be counted on to hold at over 100% of the strength of the cord- age it is tied in. And the version that terminates in a two-strand version of the #880 will hold at close to 200%.

You can find numerous soft shackle analogs in Ashley’s, including in #3180, which is  made around a block with 3-strand rope. Contemporary riggers simply adapted the structure to 12-strand braided rope, and gave it the option of an adjustable eye.

made around a block with 3-strand rope. Contemporary riggers simply adapted the structure to 12-strand braided rope, and gave it the option of an adjustable eye.

In part 2 of this series, we will continue to see how Ashley cataloged the past, while equipping riggers for the future. To go to that installment, click Here

The ABK – Brion Toss Yacht Riggers

May 17, 2018 @ 6:39 pm

[…] To find out more about Ashley and his influence on rigging — and much more — you might want to see This Post. […]