Ashley & Rigging, Part 2 of 2

In the first installment we looked at the principles underlying the Ashley Book of Knots. This time we’ll take a look at some applications, as well as a sidebar on Ashley’s pioneering work on knot security. Both installments are from an essay I wrote for the book “Thou Shalt Knot,” produced by the New Bedford Whaling Museum to accompany their magnificent exhibit celebrating the life and work of Clifford Ashley.

And now on to Part 2.

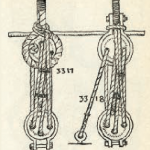

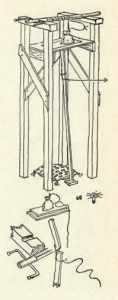

Most of the material in the ABK would be familiar to 18th- and 19th-century riggers and sailors, but that doesn’t mean it is outdated; many 20th and 21st century traditional sailing vessels, including large square riggers, have benefited from this book, notably from the chapter on Practical Marlingspike Seamanship. Here there are scores of configurations that provide modern riggers with details on basic procedures, as well as solutions to more obscure applications. This chapter concentrates on integrating rope and hardware to create, control, and manipulate structures. Thus we see rope integrated with sails, blocks, hooks, deadeyes, gammons, yards, masts, anchors, etc., as well as rope and twine integrated with each other into practical configurations (service, seizing, hitching, whipping, etc.)

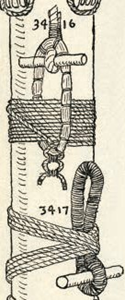

Want to know how to apply a “garland” for hoisting a top- mast? Ashley shows how, by the French as well as the English method (#’s 3416 & 3417). Need to seize a batten to a shroud? Choose from among #’s 3368-3372.

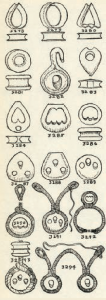

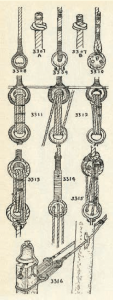

Want to know how to apply a “garland” for hoisting a top- mast? Ashley shows how, by the French as well as the English method (#’s 3416 & 3417). Need to seize a batten to a shroud? Choose from among #’s 3368-3372. Need to install some deadeyes? Take a deep breath and study # 3278 – 3318. There you will see representative examples from the beginning of the 17th century on, complete with commentary on configuration and installation, including an elegant emergency repair variation (#3302).

Need to install some deadeyes? Take a deep breath and study # 3278 – 3318. There you will see representative examples from the beginning of the 17th century on, complete with commentary on configuration and installation, including an elegant emergency repair variation (#3302).

These items, along with the almost 400 others in this chapter, might seem to have no use in contemporary rigs, but many of them have direct application today, because rigs are now, after a century-plus of hiatus, once again being made with rope – high-modulus rope, out of fibers like Spectra and Vectran – but rope nonetheless, which is unsuited to the machined terminals used on wire, but which does reward the use of creative marlingspike skills. Practical Marlingspike Seamanship is a database of ocean-proven practices that today’s riggers are regularly digging into. As a final example, consider the Selvagee (#3147), which has nowadays been reincarnated for industrial use as the ubiquitous round sling, as well as shackle-replacing “loopies,” and even as standing rigging, made out of high-modulus fibers.

Nor is this the only chapter being mined; Miscellaneous Holdfasts (chapter 26), Occasional Knots (chapter 27), and Lashings and Slings (chapter 28), could all have been rolled into a chapter called “Not Quite Ready for Practical Marlingspike Seamanship.” Here we have rope interacting with bottles, bags, bollards, bridles, blubber, and barrels, as well as hammers, flags, flag poles, tennis nets, sounding leads, thwarts, and much more.

Nor is this the only chapter being mined; Miscellaneous Holdfasts (chapter 26), Occasional Knots (chapter 27), and Lashings and Slings (chapter 28), could all have been rolled into a chapter called “Not Quite Ready for Practical Marlingspike Seamanship.” Here we have rope interacting with bottles, bags, bollards, bridles, blubber, and barrels, as well as hammers, flags, flag poles, tennis nets, sounding leads, thwarts, and much more.

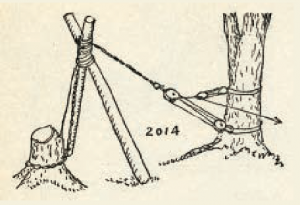

To study these chapters is to see the possibilities of rigging. You might never need to secure a stuns’l tack block to the end of its boom (#1930), but the principle behind this entry – toggling – is nowadays integral to the design of many high-tech racing blocks. And while you might never need to pull a stump out by its roots (#2014), the principles behind this entry underlie all of rigging. This little drawing, and its accompanying text, is a highly-condensed treatise on vectors, leverage, compound leverage, elasticity, tension, compression, shear, and ingenuity (don’t have a set of lashed-together spars? Use an old door).

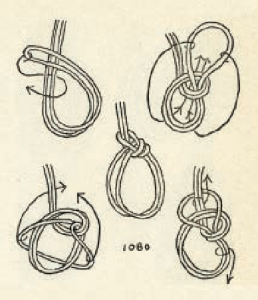

But then, it is hard to find a chapter that doesn’t have at least something of value to riggers. Even the Tricks and Puzzles chapter has tips on, among other things: the unreliability of the Clove Hitch; descending a cliff with a too-short rope; novel and sometimes useful methods for tying the Bowline and the Sheet Bend; restraining a prisoner; and escaping from restraints. The latter (#’s 2613 and 2614), are two of many topological exercises in this chapter. Of course, all knots are miracles of topology in action, but some fairly esoteric manipulations play a surprising role in many rigging applications, from the forming of knots like the Bowline on a Bight (#1080), to “dipping” multiple mooring line eyes for easy removal, to locking Brummel knots, much used in single-braided rope.

Speaking of braided rope, Ashley only mentions it briefly (#232), but you will find dozens of braids in his book, from 3 up to 61(!) strands. Flat braids, square braids, round, half-round, triangular and oval braids. Braids used for utility, or for decorative purposes only. A profusion of braids, published just before the development of industrial-scale machinery caused single- and double-braid ropes to explode onto the scene, transforming rigging utterly. Braided rope can be stronger per diameter than laid rope, as well as less elastic, more resistant to hockling. It fits better on winches, and can be “tuned” as it is braided to create ropes that cover an historically unprecedented range of desired characteristics. And it can be laid up from advanced materials that are many times stronger than steel per pound. And Ashley completely missed the boat on modern rope construction as well as modern rope materials.

Speaking of braided rope, Ashley only mentions it briefly (#232), but you will find dozens of braids in his book, from 3 up to 61(!) strands. Flat braids, square braids, round, half-round, triangular and oval braids. Braids used for utility, or for decorative purposes only. A profusion of braids, published just before the development of industrial-scale machinery caused single- and double-braid ropes to explode onto the scene, transforming rigging utterly. Braided rope can be stronger per diameter than laid rope, as well as less elastic, more resistant to hockling. It fits better on winches, and can be “tuned” as it is braided to create ropes that cover an historically unprecedented range of desired characteristics. And it can be laid up from advanced materials that are many times stronger than steel per pound. And Ashley completely missed the boat on modern rope construction as well as modern rope materials.

If I had opened my copy of the ABK for the first time today, and seen that it said next-to-nothing about braided rope, I probably

If I had opened my copy of the ABK for the first time today, and seen that it said next-to-nothing about braided rope, I probably  would have put it back on the shelf, and looked for something more pertinent to my trade. And it would have been my loss. I would have been like a physicist ignoring Newton, because he had nothing to say about quarks, or a director ignoring Orson Welles because he never used a green screen. Like those worthies, Ashley was a technician, but also, literally, an artist, who saw and described things in a way that no one else had before, and who made possible the advances that came after his time. If he had lived just a few years longer, he no doubt would have recorded/invented/speculated on the vast new field of possibilities that was opened with the revolution in braided rope: new knots, new splices, new configurations, new ways to handle new types and magnitudes of loads. But while it is true that we lost his direct input, his greatest contribution, even in his day, was not that his book was utterly encyclopedic, but that it provided a powerful way to approach knots. It can no longer lay claim to containing “Every practical knot,” as the subtitle on the cover still claims, but that hardly matters, because Ashley concentrated so fiercely on the rest of that subtitle, which reads, “What It Looks Like, Who Uses It, Where It Comes From, and How to Tie It.” If there had been room for a longer subtitle, the publisher might well have added, “What It Is Good For, Which Ones You Probably Want to Avoid, Which Ones Look Archaic or Silly But Might Just Surprise You With How Useful They Become Some Day, and Why You Should Be Studying All of This So That You, Too, Can Make Meaningful Contributions to This Ancient Body of Knowledge, Or At Least Help to Keep It Alive.”

would have put it back on the shelf, and looked for something more pertinent to my trade. And it would have been my loss. I would have been like a physicist ignoring Newton, because he had nothing to say about quarks, or a director ignoring Orson Welles because he never used a green screen. Like those worthies, Ashley was a technician, but also, literally, an artist, who saw and described things in a way that no one else had before, and who made possible the advances that came after his time. If he had lived just a few years longer, he no doubt would have recorded/invented/speculated on the vast new field of possibilities that was opened with the revolution in braided rope: new knots, new splices, new configurations, new ways to handle new types and magnitudes of loads. But while it is true that we lost his direct input, his greatest contribution, even in his day, was not that his book was utterly encyclopedic, but that it provided a powerful way to approach knots. It can no longer lay claim to containing “Every practical knot,” as the subtitle on the cover still claims, but that hardly matters, because Ashley concentrated so fiercely on the rest of that subtitle, which reads, “What It Looks Like, Who Uses It, Where It Comes From, and How to Tie It.” If there had been room for a longer subtitle, the publisher might well have added, “What It Is Good For, Which Ones You Probably Want to Avoid, Which Ones Look Archaic or Silly But Might Just Surprise You With How Useful They Become Some Day, and Why You Should Be Studying All of This So That You, Too, Can Make Meaningful Contributions to This Ancient Body of Knowledge, Or At Least Help to Keep It Alive.”

Sidebar: Testing Knots

In the first chapter, after some extensive remarks on the history and idioms of knotting, Ashley describes a series of tests he conducted on knot security (#’s 63-68), a consideration that was quite novel in his day. The test was of bends, with each knot tied in extraordinarily slick, springy mohair. Rather than a steady pull, each of ten bends was subjected to “… a series of uniform jerks, applied at an even rate of speed, using the drip of a faucet for a metronome.”

Ashley & Rigging, Part 1 of 2 – Brion Toss Yacht Riggers

May 17, 2018 @ 6:23 pm

[…] In part 2 of this series, we will continue to see how Ashley cataloged the past, while equipping riggers for the future. To go to that installment, click Here […]