On the surface, being a bosun is a matter of technical skill. You are expected to know all the knots, seizings, splices, etc., that might be needed in a given vessel, as well as how to apply those structures meaningfully to every rig component. You are expected to have a mental map of the location of every block, shackle, fairlead, and turnbuckle in the rig, every piece of running and standing rigging, on every spar. You are probably also expected to have a similar level of knowledge in hull- and sail-related matters, and to supervise anchoring and mooring exercises, and to be in charge of small boat operations. Plus, as my friend Raven notes, when the going gets tough, and disaster is rapidly unfolding, you are expected to know exactly where the appropriate tool or spare part is, and how to make things right while everyone else is panicking.

Put another way, you, the bosun, must understand the vessel as a series of systems, and to know – viscerally and intellectually – how they function, how they relate to one another, and how to keep them all in optimal condition. As if that weren’t asking enough, a bosun should also be strong, tough, and agile enough to carry out any and all needed work, and to do so with an unreasonable level of skill. This is a high calling.

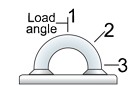

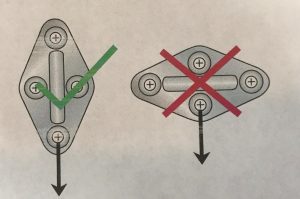

The best bosuns realize that there is a lot of theory behind all of the artisanal activity. Vessels are engineered structures, and if you don’t have at least some notion of the basic principles of that engineering, you are just blindly doing handwork. Therefore, while it is important to expand and hone your manual skill set, it is equally important that you study math, particularly geometry. Your rig is an energy-catching machine, and you cannot make meaningful, consistent use of its potential unless you understand the nature and magnitude of the loads that it will bear, and how it makes use of those loads. Acquaint yourself, if you haven’t already done so, with the forces in the rig and hull – tension, compression, torque, shear. Familiarize yourself with righting moments, metacenters, load algorithms, and all the other opaque-at-first technical descriptions which, for the bosun, can be pathways into the beating heart of the rig. If you can do that, you might, for instance, be able to choose the correct cordage, spar, hardware, etc. for any job, as opposed to cloning a previous mistake. Hmm, a very high calling. But there is even more.

A bosun is also a manager, not just of jobs, but of people. You need to be able to train your crew to do things right. You need to assign jobs commensurate with skill levels, to schedule jobs so that they don’t impede vessel operations – or get in the way of other jobs. And you will need to be able to deal with the crew’s inevitable struggles/recalcitrance/doubts, to monitor the crew without fussing over them, to trust them to do their best, but also to make sure that their best is good enough.

You won’t have time to educate each crewmember in detail, but you must give them at least enough of an outline to kickstart a learning curve. And you must give them enough consistent, compelling evidence of your own competence that they will accept that you know what you are talking about. They must have some reason to believe that what they are being asked to do is best for the boat, even if they don’t understand why.

Next, a bosun works within a financial context, especially in noble-but-impecunious non-profit organizations. Even on well-funded vessels, your ideals will, on a regular basis, come up against a shortage of cash, or time, or both. Prioritizing for safety, sailing efficiency, long-term savings, short-term savings, and good old aesthetics means that you will be juggling considerations every day, in an effort to keep the vessel running. Too many bosuns ignore things until they break, or concentrate solely on the aspects they think they understand best, or get in the habit of putting out fires as a standard working mode. Good bosuns are aware of the the budget as a whole, as well as the rig as a whole, and they do what they can. This involves a certain number of hours of spent staring at the overhead on your off watches, trying to figure out how to hold things together. It also involves a certain level of skill at lobbying the skipper, the mates, and the folks back in the office.

One more important consideration, pretty much unprecedented in the history of bosunry, is the matter of gender. Historically, sailors were almost exclusively men. Not any more. As a result, today’s male bosuns are faced with the challenge of overcoming millennia of cultural conditioning; basically they need to learn how to treat women sailors as though they were, um, sailors. They have it easy. At risk of mansplaining, I will note that this is a more difficult issue for women bosuns, even in the relatively enlightened atmosphere of the sailing community. Women know, a lot better than I, that they are unlikely to get the same level of respect that a male of equal skill would automatically receive. Quite a few vessels have achieved gender parity, or something like it, but I would be remiss not to bring the subject up, as it is one of those things that, like race, sexual preference, etc., can for no good reason affect the safety and well-being of the ship, and of the crew. I asked Julia Briggs, one of our riggers, if she had any advice for women on this topic. She used to work as a commercial diver, and that is one of the most preposterone-heavy vocations on earth. She said that, among other things, it is amazing what a difference it can make if you can offhandedly, seemingly effortlessly, pull off some feat of strength or skill or agility. It doesn’t have to be a superhuman effort, but when people don’t expect you to be able to do anything, you have the opportunity to use obvious ability to shatter their misperceptions.

In conclusion, I would like to deal with a bit of etymological misperception. The word “bosun” is a corruption of “boatswain,” and the word “swain” is generally understood to mean “sweetheart,” or “lover.” Given the irascible, notably non-romantic nature of most of the bosuns I have known, the term might be assumed to be deeply ironic. But “swain” is from the Old Norse, and originally meant “attendant.” Bosuns are, and always have been, deeply committed to their vessels, not as moon-eyed lovers, but as stolid, skeptical servants of an absurdly demanding master.

The preceding is a much-expanded version of correspondence with Erika McDowell, serving as of this writing as bosun in the brig Lady Washington. Although I have watched, worked with, and at least sometimes admired bosuns for my entire professional career, I have never been one; it is a much bigger set of shoes than I could ever hope to fill. But my particular skill set overlaps with the aloft portion of the bosun’s, hence the correspondence, and the rigging-heavy slant of what I had to say.

If you enjoyed this essay, you might like to explore my previous blog posts. Warning: some of them have nothing at all to do with sailing, but you might enjoy them anyway.

If you are interested in learning rigging skills, you will find books, videos, classes, and more in our Catalog.

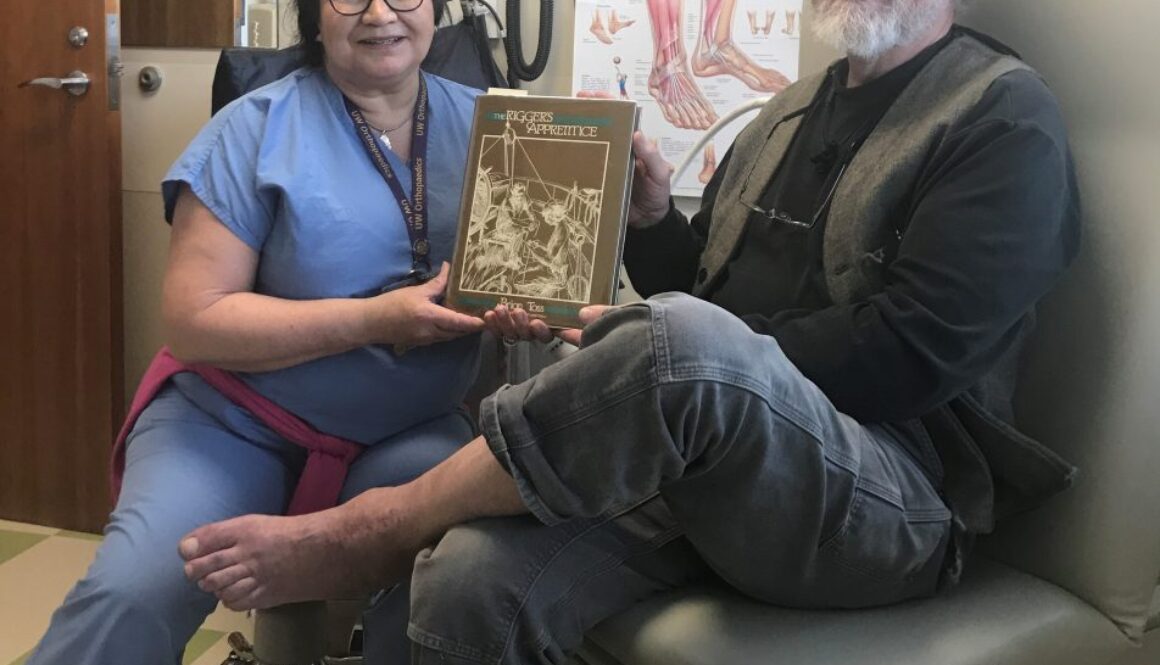

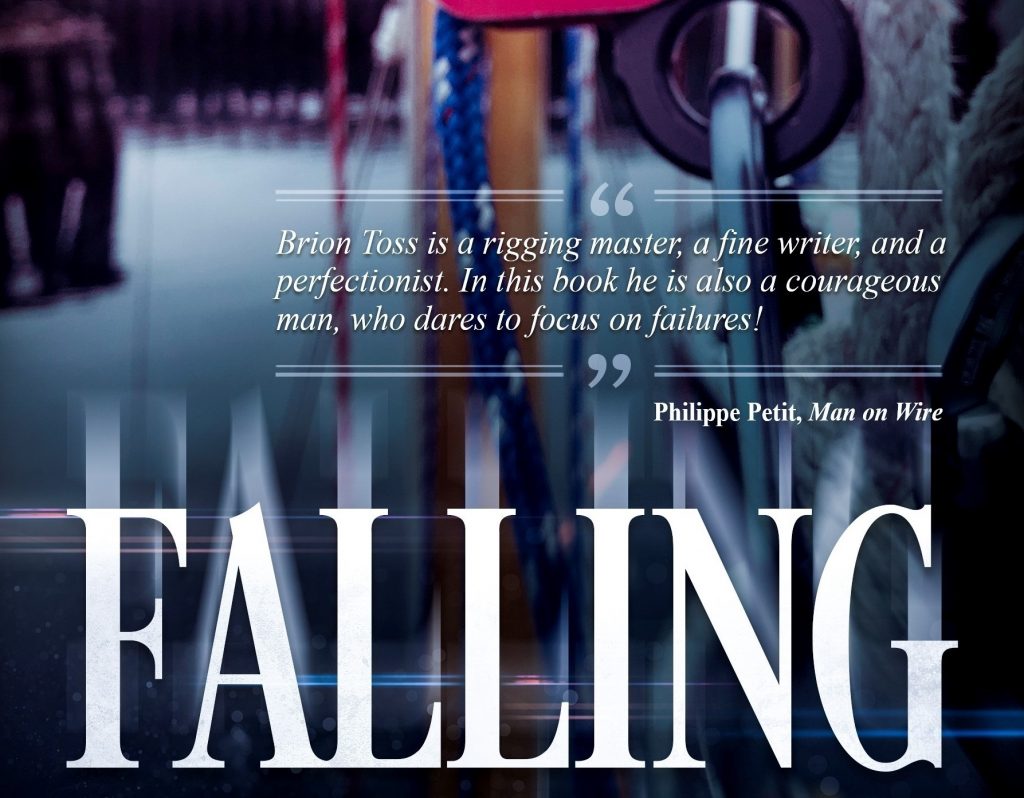

And speaking of being aloft, my most recent book is called Falling, a series of non-fatal stories about the perils of life aloft. You can find the ebook and audiobook through Amazon and Apple. If you would like a printed copy, complete with autograph, write to catalog@briontoss.com, or call 360-385-1080.PS,Shortly after I posted this article, Maggie Ostler, of the barque Picton Castle wrote to tell me about their Bosun School. If you or someone you know aspires to this high calling, this might be a link for you:

https://www.picton-castle.com/bosun-school.html

Fair Leads,

Brion Toss